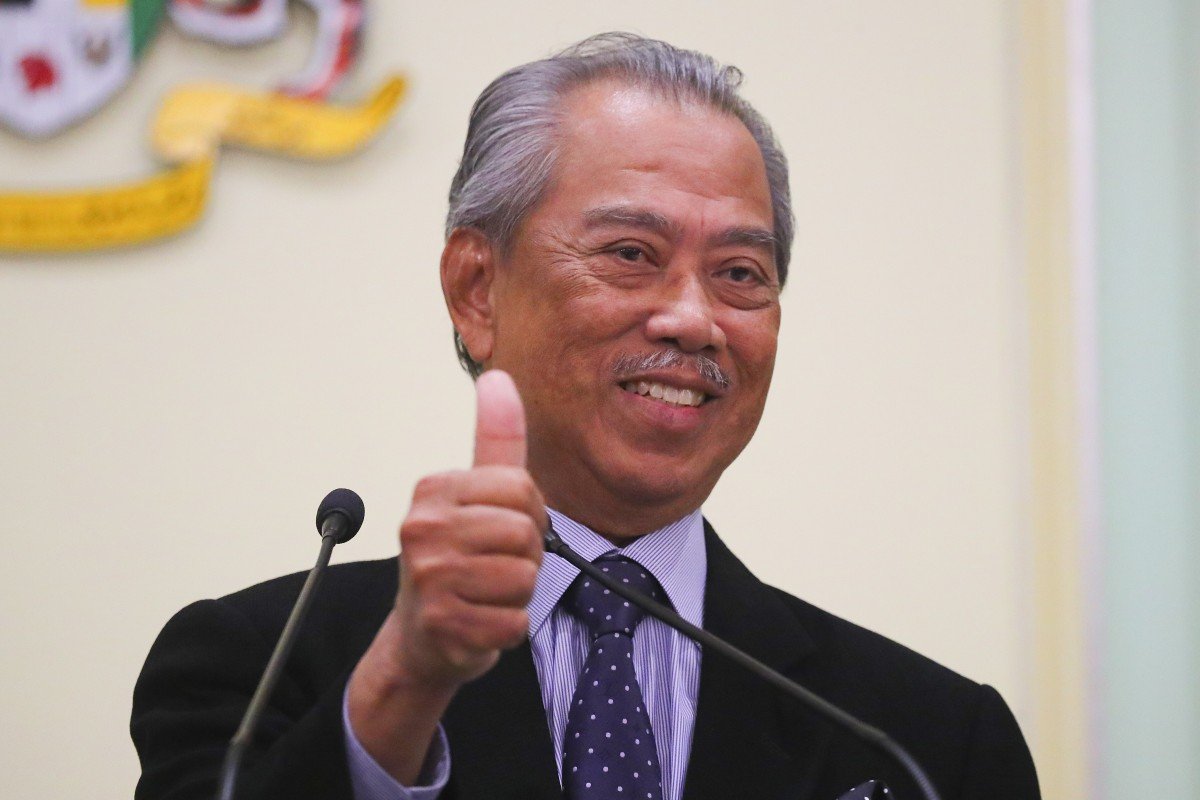

In April, the Shah Alam High Court ruled in favour of a Sabahan who was arrested last year for allegedly distributing drugs on a writ of habeas corpus, citing, among other reasons, the fact that the name the minister used to sign the detention order – Tan Sri Muhyiddin Mohd Yassin – was invalid.

From the outset, the case was already difficult in the first place due to a lack of possible grounds for judicial review. There is already a tendency of the courts to defer to the government in cases involving detention, the deprivation of liberty and other issues of national security. Besides looking into the technical compliance of the detention, there is not much else the Court can review. The bodies that make decisions of national security have their own procedures and rules (some of which may even exclude judicial review outright), making it hard to challenge such decisions.

As such, in national security & personal liberty issues, the Courts are therefore usually only left with matters of technical non-compliance to review.

There is no requirement under the Ministerial Functions Act or the Federal Gazette that a document must be signed by “Mahiaddin” instead of “Muhyiddin” (however to prevent any future complications, Malaysia’s government has recently issued a directive ordering all civil servants to use the legal spelling of the prime minister’s name). And as all who are in the legal business will know, technicalities are rarely fatal; a simple correction can be made to remedy the technical mistake.

That being said, in a habeas corpus application, a “technicality becomes important” as my learned fellow member of the Bar, Andrew Khoo puts it, when the case “involves a person’s liberty”. Moreover, bear in mind that the Minister’s usage of the wrong name was only one of a number of other reasons the Court gave for the quashing of the detention order; for example, the counsel also pointed out that there was a major delay in completing and submitting the full police report to the Minister and his MInistry, violating Section 3(3) of the Dangerous Drugs (Special Preventive Measures) Act 1985. In short, while the defective signature was not the deciding factor, it could not be overlooked due to the nature of the case.

This has caused some people to wonder if any of the orders/directives signed by the Prime Minister in the past will now be held void. Bear in mind that the Prime Minister has had a lengthy career; considering his past tenures as the Deputy Prime Minister, Home Minister, Education Minister, all the way back to his time in office as the Menteri Besar of Johor, he has signed countless orders/directive under the name “Muhyiddin”; more than a handful of them were made in relation to issues of national security; some of which are still in force today. To invalidate them now would unleash a wave of administrative chaos. So how do we prevent this?

Simple: a law, order, or ordinance cannot become void simply because it has procedural improprieties (ie. the wrong name); it only becomes void after someone challenges it in Court, and the Court declares it void. This is a canon applied universally; subsidiary legislation are assumed to be valid even if it goes beyond the scope allowed under the parent act until declared void by the doctrine of substantive ultra vires. Case in point, Section 3(3) of the Sedition Act only became void after it was challenged in Court and declared unconstitutional; the list goes on.

A law, order, or ordinance cannot become void simply because it has procedural improprieties (ie. the wrong name); it only becomes void after someone challenges it in Court, and the Court declares it void.

Therefore, all the Minister’s previous orders and directives where he signed off as “Muhyiddin Yassin” are still valid; there is no harm done; save for some embarrassment the situation has caused.

It has been made known, however, that the Prime Minister will use his legal name from now on. In fact, he had used his legal name to sign off four proclamations of emergency; namely the national emergency, and the ones in Batu Sapi, Gerik and Bugaya to suspend by-elections.

The quashing of the detention order due to the signing of the detention order by the Minister with a ‘glamour name’ really highlights how extremely ‘protective’ the Malaysian judiciary is when it comes to individual liberties. This will ensure that the State cannot simply interfere with such sacrosanct matters with a lackadaisical attitude; instead, they are made to strictly follow the rule and qualifications in order to take such drastic measures.

The quashing of the detention order due to the signing of the detention order by the Minister with a ‘glamour name’ really highlights how extremely ‘protective’ the Malaysian judiciary is when it comes to individual liberties.